Some ways to identify first and early impressions

First and early impressions best convey the intentions of the artist and publisher. High quality impressions can be identified by clear, unbroken key-block outlines, especially on any faces or title cartouches; visible wood-grain – the ‘finger print’ of every Japanese print and the depth of impression, which can often be sensed with the fingertip, especially when thicker, or deluxe hosho was used. The following techniques are indicative of and are best demonstrated on only the earliest editions: Bokashi – subtleties of careful gradation, sometimes merging colours one to another or shaded to give form and depth. Fukibokashi – the spraying of pigments or the splashing of gofun (white pigment). The addition of rice flour or mica to give sparkle to colours.

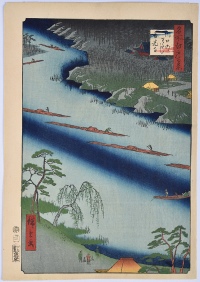

Example of a First Edition Print: Ichiryusai Hiroshige – “Ferryboats to Zenkoji Temple at Kawaguchi”

How many impressions were produced?

Dealers in ukiyo-e are often asked how many impressions were produced or what is the edition? This is a difficult question to answer because of the limit to the information available to us, however the writings of Mr Tokuno (1893)[1] and Mr Watanabe(1936)[2] give us good insight into the printing process and the number of impressions produced.

Before the 20th century, no Japanese print was numbered except to denote the chapter in a series or a station on a highway. In the 19th century mainstream print production was structured to sell as many copies as possible for modest amounts – some prints being sold then for the cost of a bowl of noodles. Ukiyo-e can be seen to have been one of the most democratic art forms and vast numbers of prints were produced.

The consensus of opinion is that ‘editions’ (ippai) of around 200 prints were pulled concurrently. The number of editions were increased, sometimes substantially, according to the popularity of the design.

Depending on handling and the choice of wood for the block and the pigments used it was possible to produce large numbers of impressions before any discernible deterioration became evident. Too many impressions taken together caused greater wear-and-tear on the blocks and it was beneficial to allow the blocks to rest for several days between impressions. Blocks saturated with pigment became sluggish and erratic in relinquishing the colour evenly. Some pigments, due to their gritty nature, caused deterioration of the blocks.

With optimum handling, printing in excess of 4,000 would have been perfectly feasible before any deleterious signs showed. It is likely that the print numbers for the most popular designs could have been in the region of 20,000. Mr Tokuno, writing in the late 19th century, states that 3,000 sheets could be produced per 8 hour day from the key-block, and around 1,200 to 1,800 from a straight forward colour block, while a colour block needing gradation gave 600 to 700. Experienced printmakers worked with great speed to generate these numbers of prints- it is estimated that to ‘pull’ a colour print it took from 15 to 25 seconds. On the other hand, Roger Keyes’ “guess” at the probable editions for verse surimono, based on a surimono in the British Museum showing a packet of surimono, is 75 to 100 impressions[3].

In the late 19th century wood block printing was competing with copper-plate engraving and photography. There is evidence to suggest that to give even greater speed and quantities, two (or perhaps more) identical designs were cut side by side on the same block and printed simultaneously[4].

[1] – T. Tokuno, chief of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (Insetsu-Kioku) of the Japanese Ministry of Finance. The Smithsonian Institute, US National Museum, Washington, 1893. Description of the woodblock process, p. 232.

[2] – Watanabe, Catalogue of Wood-Cut Colour Prints, Tokyo 1936, p 72

[3] – Roger Keyes, The Art of Surimono, Sotheby Publications, 1985, pp 36/37, fig. 14

[4] – Comparing impressions of prints by Yoshitoshi for the Yamato Newspaper [publisher: Yamato Shimbunsha; series Kinsei Jimbutsushi, dated: 1886 – 1888] reveals discrepancies in the key-block outline and elsewhere between identical designs which could only be result of re-cutting.